Very few people dispute the brilliance of the Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan series: twenty-four novels and comics published in fifty-two languages in the last century with some two billion readers, turning Tarzan and his main squeeze, Jane, into one of the most iconic couples in literature. The late Ray Bradbury, himself deeply influenced by ERB, commented, “I love to say it because it upsets everyone terribly—Burroughs is probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world.”

Tarzan was the very first superhero. The ape-man pre-dated Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man. In a way, he was the first “super-natural” hero, though his powers were altogether human and emanated from the natural world. He possessed neither extraterrestrial attributes nor cool technology, but—having been raised by a tribe of “anthropoid apes”—he was the strongest man on earth, could “fly” through the jungle canopy, and speak the languages of wild animals.

Moreover, his native intelligence and nobility of spirit were such that in spite of being abducted from his human parents at age one, then speaking nothing but the simplistic, gutteral Mangani language, he was able to teach himself to read and write by studying the “little bugs” (words) on the pages of book in his parents’ deserted beach hut. Indeed, by the end of the first in the series, Tarzan of the Apes, little Lord Greystoke could speak fluent French and English and was driving an automobile around the American Midwest. By the end of the series he moved comfortably between the civilized world and the dark, dangerous jungle, explored inner earth (riding on the backs of dinosaurs), had flown in WWII for the RAF, and ultimately mastered eight languages.

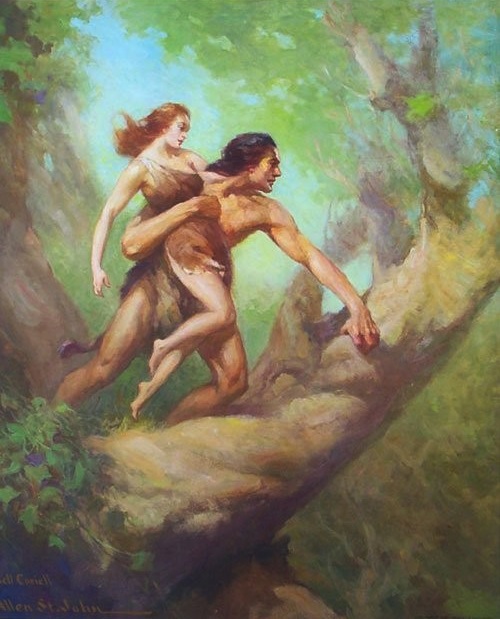

Hollywood couldn’t wait to get their hands on this wildly popular figure and the woman who—while never managing or wishing to tame him—stole his heart. The love affair between Tarzan and Jane allowed the movies a romantic core. Tarzan personified the ultimate heroic male lead—virile, savage, insanely strong…and next-to-naked. Jane Porter was the perfect female foil—squeaky clean, highly civilized and a virgin when they met. Their romance, far from prying eyes in the steaming jungle, spat in the face of convention and sizzled with primordial passions.

The 1918 silent film Tarzan of the Apes attempted to remain faithful to ERB’s story of the same title. We see the marooning of Lord and Lady Greystoke on the west coast of Africa, little Lord Johnny’s birth, his parents’ murder and the infant’s “rescue” by Kala, the female ape that ultimately raises him. In the first half of the movie, an entirely naked child actor (Gordon Griffith) cavorts among the creatures in monkey suits, the steaming Louisiana bayou where it was filmed, substituting for the African jungle.

In the second half, Tarzan becomes a man played by the large, barrel-chested Elmo Lincoln (suffering the worst bad hair day in cinema history) and is discovered by a treasure-hunting expedition. Among the explorers is an 18-year-old Jane Porter, played by the star of stage and screen, Enid Markey, accompanying her father and looked after by her maid, Esmeralda. Amidst the mugging and overacting so typical of silent films, Tarzan falls for Jane (despite the ugliest dress ever seen onscreen) and Jane, endlessly swooning and terrified, goes ape for the Lord of the Vine.

But it is here that the books and movies begin to diverge. Several novels into the series ERB—clearly unhappy with the female character he had created—actually kills off Jane Porter (now Lady Greystoke). When Tarzan returns to their Kenyan home after a jungle adventure, he finds his murdered wife’s charred body in the ruins of their house. But this literary assassination touched off a firestorm in Burroughs’s personal and professional life. His wife was furious, his publisher alarmed. Readers liked Jane. They adored the romance. So Burroughs caved, and went on to include Jane in a few more novels, though after Tarzan the Terrible (1921) he’d had enough of her, and the ape man went on alone—never, however, succumbing to carnal pleasures with any other woman, no matter how luscious or seductive.

With the first of the Tarzan “talkies” starring the big, buff Olympic gold-medal-winning swimmer Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan, and the gorgeous, sassy movie star Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane, the love story became cemented in the consciousness of every Tarzan movie-goer until the present day.

It didn’t matter that Tarzan was reduced to a linguistic simpleton who could master no more than basic nouns and verbs in English. O’Sullivan’s Jane was a 1930s sophisticate plopped down in the African jungle. Mesmerized by the wildman, her civilized values fell away (along with her clothes) so that by the end of 1932’s Tarzan the Apeman, the two were engaged in off-screen, out-of-wedlock sex.

The amazing second unit wildlife footage from Africa and a famous wrestling match with an alligator were less thrilling to audiences than Jane’s skimpy leather two-piece outfit (under which she could not possibly be wearing underwear). In 1934’s “Tarzan and His Mate,” the infamous four-minute underwater swimming sequence shows Tarzan’s privates covered by a loincloth, but Jane (O’Sullivan’s body double, here) swims sinuously and sensuously and entirely nude!

Back in those days this couldn’t have been more shocking (or welcome) to audiences, though the scene galvanized an until-then-toothless board of Hollywood censors, who took the opportunity to edit the offending sequence. And from then on, Jane’s costumes were high-necked little housedresses that revealed nothing more than bare arms and legs. The pair became more and more domesticated until they seemed downright suburban. The grass “nest” in the crotch of a tree was replaced by a large, tricked-out tree hut with rustic furniture and an elephant-driven elevator (no climbing required). Because filmmakers refused to marry Weissmuller and O’Sullivan, their son, “Boy,” was an orphan they found on a crashed plane. Wild sexual couplings were left entirely to moviegoers’ imaginations. The whole tame set-up reached its nadir when Jane, standing in front of her tree-house, hands on hips, says to her adopted son, “Boy, go down to the river and get me some caviar and I’ll put it in the refrigerator.”

While the Weissmuller/O’Sullivan movies became the blockbusters of the ‘30s, and had millions of men fantasizing themselves as Tarzan and women as Jane, not everyone was so impressed. World-famous primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall not only credits her choice of profession to the reading of all twenty-four of ERB’s Tarzan novels, but also, as a ten-year-old girl, fell in love with the ape man, and was horribly jealous of Jane. Goodall considered Jane Porter “a wimp,” believing that she would have made a better mate for Tarzan than her namesake! And her reaction to the movies was extreme: “My mother saved up to take me to the Johnnie Weissmuller film…I’d been in there about ten minutes when I burst into loud tears. She had to take me out. You see, that wasn’t Tarzan. In those days I read the books. I imagined Tarzan. When I saw Johnny Weissmuller, it wasn’t the Tarzan I imagined.”

Edgar Rice Burroughs himself was displeased with the movies adapted from his books as well. But as they made him the fortune he’d always dreamed of having, and the characters he’d created transformed into an unstoppable cinematic juggernaut, he watched in astonishment as the twentieth century continued to churn out nearly one hundred films…some of which we’ll discuss tomorrow in “Part II: Will We Ever See A Great Tarzan Movie?”

Robin Maxwell is a screenwriter and the bestselling author of eight novels of historical fiction. On September 18th Jane: The Woman Who Loved Tarzan will be published by Tor Books. It is fully authorized by the estate of Edgar Rice Burroughs and the first Tarzan classic ever told from Jane’s point of view.

Ahhhhh Tarzan novels! They, along with Heilein juveniles were my first foray into serious reading of SF/F. In fact, I just remembered, the first one I ever read was my father’s ancient copy of one at my grandmother’s house that I read in desparation due to boredom…

I re-read Tarzan a few months ago for the first time since I was around 8 and I was shocked at how smart Tarzan was; I had completely forgotten that aspect. Then I saw one the movie “Tarzan and His Mate” and came out spitting mad. My friend could not understand why the movie made me so mad until I explained the differences between the intelligent Tarzan we got in the books and the idiot in the movie. I’m fine with Tarzan not being super intelligent in the movies, but if he’s been living with Jane for over a year, then someone with even average intelligence would speak better than he did! I’m really looking forward to the next post as I’ve been wondering about that…

Tarzan, such nostalgia. I read like 8-10 books when I was in fourth and fifth grade. In retrospect they are not only deeply racist and full of misogyny, they also fail biology big time.

But they are also so fun to read. And in an odd way *because* those books are not serious and cannot be taken seriously in *any* context (be it historical, cultural, anthropological or biological) it’s easy to ignore these problematic aspects and focus on Tarzan and co. solving riddles, fighting conspiracies, killing lions and etc.

And it took three whole comments to get to the racsim. That’s a record for commentors here.

Desultorily started a reread a few months back (I had read about 15 of them, almost 20 years ago, in random order) and am now at “Leopard Men”. The number of times he flexes his mighty thews and sinews…sigh…and his method for dealing with lions is so repetitive, one day he’ll meet a smart lion and then….

…but they’re fun in the same way as Doc Smith’s space operas. Tarzan bundolo kreegah!!

lakesidey

(who is going to pretend the movies never happened)

Rowanmdm3: When I was doing research for JANE: The Woman Who Loved Tarzan, the ape-man’s ability to learn to speak well was one of the first things I bumped up against. If feral children don’t hear human language during what is called “the critical period,” once they come back into civilization, they NEVER learn to speak properly. I also thought it impossible to believe that Tarzan would be able to teach himself how to read and write. That’s why I convinced the estate of Edgar Rice Burroughs to allow me to change little John Clayton’s abduction by the Mangani from a year-old boy to four-years-old. Thus, when he meets Jane and spends some time with her, it’s more a matter of recovering lost memories of speech and “civilized interactions.” As for the Tarzan of the movies, while I loved him as a ten-year-old, as an adult I found his simpleton persona truly annoying.

Xiao: At two Tarzan Centennial Celebration in Tarzana, CA and a two Tarzan panels at the San Diego Comic-Cons, the questions of racism and misogyny came up repeatedly. Die-hard fans believe ERB and Tarzan were simply products of their time. Tarzan’s hatred of a nearby native tribe is justified by the fact that one of the tribesmen had killed Tarzan’s beloved ape-mother, Kala. Even so, in reading stories of the ape-boy’s youth – JUNGLE TALES OF TARZAN – there are a disturbing number of references to him enjoying “baiting the blacks.” Now having studied ERB extensively, and as a woman very sensitive to misogyny, I don’t consider him a woman-hater.

Lakesidey: In an interview at the same convention, Jane Goodall recalls how horrified she was when, recently, she re-read some of her beloved Tarzan novels and realized how brutally violent they were, and how many jungle animals Tarzan killed.

Count me among those who think Burroughs was a product of his time, and in some ways, a bit more enlightened than his counterparts (Jane and Dejah Thoris are no shrinking violets, for example). Bigotry and racial superiority was so much part of the culture of the time, and attitudes and assumptions have come such a long way even in my lifetime.

Regarding the divide between books and movies, like many a book and movie that diverge, I look at them as ‘alternate universes,’ familiar in some ways, but different in others. I try not to think of one as undercutting the other. For example, I love Constable Hamish MacBeth in book form, and loved the old BBC TV show, even though the character, and the village people he interacts with, are strikingly different in the different media. And I always enjoyed Johnny Weissmuller and the sly humor he brought to the role. And oh, that beautiful Maureen O’Hara, the first movie star I ever fell in love with.

This discussion reminds me that I never read all the Tarzan books, only the half dozen or so that we had in our house. A good idea for a winter reading project!

After reading Tarzan of the Apes for the first time in my life last year, I’ve concluded that Tarzan grew up amongst a remnant band of ardipithecines.

Tarzan of the Ardipithecines – that has a certain ringto it.

I’m an ardipithecine, ardi-ardi-ardipithecine!

etc

Grey: Wow! You hit the nail on the head with “Ardi.” That was the species I decided the Mangani were – a “living missing link” species. The National Geographic Magazine (July, 2010) that reported her (with that amazing illustration of what she would have looked like) was hung above my desk the entire time I was writing JANE. In fact, my character Jane, and her father are paleoanthropologists looking for Darwin’s missing link in Africa in 1905 when she happens upon Tarzan and the Mangani. Ardi, and her discoverers, are acknowledged in my “Author’s Note.”

Alan: I appreciate your cool-headed views on ERB’s racism and misogyny. It’s really easy to point fingers and name-call. Harder to do the research into the values of other historical periods.